- Home

- George Brewington

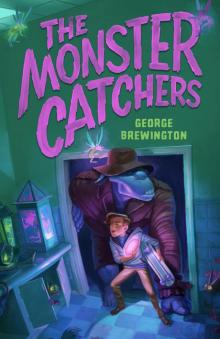

The Monster Catchers--A Bailey Buckleby Story Page 5

The Monster Catchers--A Bailey Buckleby Story Read online

Page 5

Dougie stood up straight, pushing his giant foot down harder on Canopus’s spine. Bailey couldn’t help but worry that his father, forgetting his own strength, might crush the little goblin.

His father was red with rage. “Never!”

Axel shook his head in disappointment. “You have determined your own fate, human, as usual. Rowf, rowf!” And then he fired.

Everything happened at once. A stream of red Kool-Aid sprayed onto Bailey’s father’s chest, onto which Daisy dive-bombed with sheer delight, inhaling the rich smell of sugar water, squealing, slurping, clawing with her hands and feet and biting his belly with her sharp snaggleteeth. Dougie howled, pressing his foot down on Canopus’s neck, grabbing at Daisy with one hand and his stick of dynamite with the other. Daisy let go of the stick. She didn’t care about it; she cared about one thing only—sugar. She bit and bit and bit, and Dougie’s wounds opened, his blood mixing with the Kool-Aid.

Bailey drew a neon-green Frisbee and shot it with perfect precision so that it sliced at the last moment into the cynocephaly’s neck. Choking, unable to breathe, the wind demon dropped his blaster and grasped for his throat, giving Bailey a moment to stand up and flick his last Frisbee straight into his right eye.

“Bow wow wow … owwww!” he howled, grabbing his injured eye, turning, and running into the night.

Then the goblins leapt.

They grabbed Dougie’s arms and legs, piling on him while Daisy shredded his Kool-Aid- and blood-soaked shirt with her sharp, crooked teeth. The tiny goblin dove for his right foot, trying desperately and unsuccessfully to pry it off Canopus’s neck.

“Canopus! My darling!”

“Can’t breathe … can’t breathe.”

Canopus struggled and squirmed under the big man’s weight. The goblins piling on them only made it worse.

“Can’t breathe … Help, Capella … help.”

Big-eyed Capella held Canopus’s hands and pulled and pulled, but Dougie’s foot was firmly planted on her beloved’s neck.

Bailey tried to drag the goblins off his father, but there were too many in the pile. He feared his father would suffocate and bleed to death if left much longer. But Bailey had a monster hunter’s instincts. He crawled into their tent, grabbed the lantern, and then crawled back out. He stood up and turned the light to HIGH so it blazed brightly, lighting up John Hanson’s entire backyard.

He could see the goblins in vivid detail now—the boils on their green skin, the hair sprouting from their long pointy ears, the double-jointed fingers and toes that held tightly on to his father. All at once, their glowing green eyes turned toward the lantern, mesmerized. In unison, they sighed: “Oooooooh!”

“What a beautiful star!”

“Star of the night!”

“Shining so bright!”

“By our souls, we will save your light!”

The goblins squirmed off Dougie and came running toward Bailey, but before they pounced on him, he threw the lantern as far as he could into the redwoods. The goblins immediately changed direction and ran toward it. “Star light! So bright! How your light awakens the night!” They piled on the lantern, all grabbing for it and abandoning Canopus. Only Capella remained, tugging on his arm.

Daisy continued to bite and bite, while Bailey’s father cussed at the vicious little faery. But then Bailey grabbed the weighted net and scooped Daisy off him, tied a quick knot, and had her captured.

“Thank you, my boy,” he said, lifting Capella up by her ankles. She wiggled desperately to squirm free.

“No, Capella, NO!” Canopus yelled.

But Bailey’s father had them both, holding them upside down in the air, grinning with pride.

“Well, I’d call this a successful night,” he said. “Not one goblin but two. And we got the demon’s pet as well,” he said, poking his bloody finger stump at Daisy. “Come on, Bailey. Let’s go home and lock up these little wretches.”

Bailey looked at his father, soaked in blood and Kool-Aid, his shirt shredded, his wounds bleeding as he held a goblin by the ankle in each hand, his sweaty shag of rusty hair in his eyes. For a moment, Bailey saw his future. In twenty years, would he be soaked in blood, missing a finger, holding captured, frightened monsters upside down by their ankles? He wondered—would his mother approve? But she was dead and his father was alive, so he told himself it was childish to guess.

CHAPTER NINE

THE WONDERFUL LIGHTED PAINTBRUSH THAT GOD USES EVERY NIGHT

BAILEY COULD BARELY keep his eyes open. It was dawn. Abigail wanted her sardine breakfast, Henry wanted his raw chicken in ice water, and the twenty-six faeries wanted sugar, as always. The hoop snakes needed live mice, and the live mice needed kibble. The ratatoskers needed fresh vegetables from the garden. Abigail chirped like mad, the faeries squealed, and Henry barked roump, roump, ROUMP! Daisy wailed loudest of all, banging against the walls of her new iron lantern prison. She was the only white-winged faery on display, and Bailey’s father had hung her lantern high above the others from a ceiling hook and priced her for her rarity at $9,999.99. Daisy swung her lantern back and forth, screeching and spitting iron sulfate on the floor below to create tiny flashes of fire. But the two goblins—Canopus and Capella—each sat quietly in separate wire cages designed originally for large dogs, staring at the long fluorescent lights in the ceiling.

Bailey, though tired, got busy making their breakfasts. The sooner the monsters were fed, the sooner he could sleep, and the sooner he slept, the sooner he could wake up to work on his presentation for tomorrow. Savannah had texted him Are you ready?;) He had texted back Sorta.

His father, having suffered significant blood loss from his finger, had microwaved a pepperoni pizza, eaten it, and fallen asleep upstairs.

After Bailey fed Abigail and Henry and all the faeries, he came to Capella’s cage. She seemed to be more responsive than Canopus, who only stared at the fluorescent ceiling lights with his mouth gaping open, salivating, occasionally reaching his double-jointed fingers up in longing for the lights. Capella crouched in a corner of her dog cage, hooding herself in the fleece blanket Bailey’s father had given her, as if trying to resist the temptation of the shining fluorescence.

“Would it be better if I turned the lights off?” Bailey asked. “Do they hurt your eyes?”

“No, you mustn’t do that,” Capella gasped. “Stars were meant to shine. Don’t darken the stars on our account.”

“What do you mean? They’re just electric lights.”

Bailey demonstrated his point by walking to the light switch and flipping it several times to make the lights flicker. Canopus screamed in horror.

“Please don’t torture the stars,” Capella pleaded. “It’s bad enough you keep us in cages, but to starve the stars is the worst of all possible crimes.”

He and his father had never captured a monster that spoke English in complete sentences before. He felt guilty for caging such intelligent creatures.

“We put you in cages because our customer paid us seven thousand dollars to keep you off his property and stop you from stealing his lights.”

Capella grabbed the bars of her cage with her long fingers. “No one owns the stars! We were simply trying to do a good deed. The best deed! To save lives. To save the stars.”

Bailey crouched down and sat cross-legged in front of her cage. “You keep saying that, but don’t you realize these lights aren’t stars? They’re electric bulbs. They’re made in a factory somewhere by people—by human beings.”

Capella turned away from Bailey. “You humans take credit for everything. You didn’t make the stars. The stars of the night used to shine so bright. There used to be millions. Now when we look up, we only see a hundred or so. Soon there will be no stars left. You humans have knocked them all down. Someone has to take responsibility, don’t they? We are the Eighteenth Goblin Order of Star Guardians, and we mean to put the stars back in the sky before you kill them all. And before you kill all of us, too.”

Bailey scratched his head. “I think you’re a bit confused.”

“I think you’re a typical human,” Capella said. “Greedy. You say we steal, but you stole the stars first. And now you’re even stealing us. Our tunnels once stretched throughout the whole world, connecting all our tribes. Now we are separated by human construction. Your subways destroyed our homes and your sewers flooded our cities.”

Canopus stared upward, reaching his long fingers through the cage bars.

“You’re going to burn your eyes out if you keep staring. Can I get you two anything to eat before I go to sleep?” Bailey asked.

“I’m not hungry,” Capella said. “Canopus? Are you hungry? The human boy wants to feed us.”

But Canopus didn’t say a word. He still clung tightly to the bluebird night-light, which glowed from the power of a single AA battery, although his eyes remained fixed on the even brighter, blazing, eye-watering ceiling lights.

Bailey was too tired to insist, and his eyelids itched. He locked the wrought iron gate, locked the thick oak door, slid the purple curtain behind him, and dragged himself up the stairs to his bedroom.

He climbed into bed and turned to page fifty-seven of In the Shadow of Monsters, where Gobelinus cuniculus stared back at him with sharp teeth and large green eyes. Bailey read the lush words of Dr. Frederick March:

Having established camp several hundred feet below the peak of Mt. Lyell in the Sierras, I found myself slightly dizzy from the crisp thin air at thirteen thousand feet and the anticipation of my first sighting of Gobelinus cuniculus. The sun had set, repainting the big sky behind the mountain peaks in yellows, oranges, and purples. I remained half-buried in snow and dirt, trying to remain as hidden as possible, with my trusty Nikon D700 camera at the ready. Scratched-out holes in fallen redwood trees pointed me toward the subject I sought. I knew from my studies that these holes were the surface exits of tunnels that extended through the tree cores, past the roots, deep into the earth. Sure enough, as the sky grew darker, goblin heads began to appear. I remained perfectly still while one by one their heads popped out of the tree holes. They nodded to one another in greeting, their ears long and pointy and at attention. Darker and darker the sky softened and more and more goblin heads appeared. Their nightly theater was about to open. The stars began to appear, at first only a few scattered pinpoints of light above the silhouettes of mountains. I dared not even take a single photo yet for the simple fear that my camera click might attract their sensitive ears and scare them away.

I waited. More and more stars appeared, filling the night sky with light, and just as our children might enjoy the grandest fireworks display on Independence Day, they ooohed and aaahed at the show. Their excitement and laughter and amazement grew, and soon they were clapping loudly as the Milky Way burst into view and the sun disappeared entirely. Only a thin crescent of the moon remained to provide any other source of light. Humankind’s artificial light is absent in the Sierras, so the stars’ majesty could not be muted. The goblins’ clapping was excellent auditory cover for me. I began clicking my camera, capturing their rows of sharp teeth. I have never seen such an impressive display of sharp serrated teeth except on the great white shark. Their long ears wiggled in the cold night, their green eyes glowing and reflecting their love, their gods, their greatest happiness. I watched several goblins hold each other tight in warm gratitude for the display. Several smaller infant goblins huddled closer to their mothers, asking their parents about the wonder they were witnessing. Was this their own dialect of English I was hearing? I could not believe my ears! But I dared not approach any closer.

I stayed behind, although I desperately wanted to join in their reverie. I nearly shed tears for love of the stars myself, as if I was seeing them for the very first time, never before having contemplated the wonderful lighted paintbrush that God uses every night to illuminate our infinite sky. No wonder these goblins never failed to make this appointment. I stayed with them unseen until dawn, taking photographs. I did not want the accursed sun to rise, because as the coming sun’s light changed the sky from black to blue, the goblins dropped back into their holes one by one, disappearing from my sight. As dawn took the place of the night, the mountain peaks of the California Sierras—though majestic in their own right—suddenly seemed to me so lonely and far too bright.

Bailey stared at the doctor’s photos of the goblin eyes peering up at the Milky Way for as long as he could, but his own eyes were very heavy. He pretended that he himself was Dr. March, grown-up, wearing muddy hiking boots, a vest with a hundred pockets, a camera around his neck, huddled in between logs in the mountains, a discoverer of goblin hideouts and beautiful views of the stars. He wondered where the great international monster hunter was now. In the hills of Afghanistan? The jungles of the Congo? Somewhere beneath the sea? Bailey wondered if he himself would ever leave Whalefat Beach to seek out the most exotic monsters yet unknown to humans, and maybe even meet Dr. March along the way.

Bailey reached his hand down beneath his bed to find a shoebox hidden there. He opened it to remove a photograph his mother had taken seven years ago. It was a picture of Henry in diapers, blue and smiling with his long tongue hanging out. His mother really did take a good photo.

Then he turned to page 186 to Dr. March’s entry on trolls. The troll in his photograph crouched underneath a rustic bridge, its blue body camouflaged in mud, partially hidden by trees. One arm of the troll reached up the length of a tree, its long, muddy fingers blending with the overhanging branches, so that if an unsuspecting human were to attempt to cross the bridge, the troll could quickly grab the trespasser, crush his bones, and eat him whole. Long, straggly hair hung from the troll’s head, ears, and armpits. Bailey placed his mother’s photo of Henry side by side with the photo of the troll. Yes, they were both blue with long arms all right, but unless Henry was about to undergo an incredibly transformative and unfortunate bout of puberty, Bailey just couldn’t see how Henry could grow up to become this horribly hairy, sharp-toothed ugly beast.

Thinking about the mystery made him even more tired, and before he could shut the book, he was asleep.

CHAPTER TEN

BABOON BUTTS

BAILEY WOKE UP at four a.m. He had slept through the afternoon, evening, and a good portion of the night. Dread for the school day crept down his spine and into his stomach. Today was social studies presentation day.

He checked his phone. Savannah Mistivich had been texting him. Are you ready? 9:11 p.m. Then again: Hey boy are you ready? 9:29 p.m. Then one more time: Well good night you little punk! You better be writing some good stuff!;) 9:58 p.m.

He liked that she had sent him three texts. He saved them and reread them several times.

All the lights in the house were on as he went downstairs. He heard his father’s classic rock music blaring from the back of the shop, where bright light was shining from beneath the purple curtain.

The faeries snored, their tattered wings over their little heads to shield themselves from the fluorescent lights. Abigail tucked her human head down into her wings, too. The hoop snakes and ratatoskers hid in their nests of wooden shavings. Even blue Henry lay snoring in a corner of his walk-in freezer, his head covered by his feet, which twitched as he undoubtedly dreamed of chasing seagulls and lapping up sea foam.

But Bailey’s father was wide awake, sitting on a stool in front of Canopus’s cage with his sketch pad on his knee. Bailey had always liked his father’s sketches because they showed such detail and captured real monster emotion as vividly—if not more so—as Dr. March’s or his mother’s photographs. It seemed ironic to Bailey that his father’s illustrations portrayed such feeling, since he always said all monsters were evil and should be locked up. And even though Canopus had chomped off one of his father’s fingers, his sketching ability had not diminished. His portrait of the goblin was coming along nicely and looked quite lifelike.

Many of his father’s drawings had been published in the monthly ma

gazine Peculiar— a publication that catered to the small niche of monster fans who knew full well that monsters really did exist. The magazine featured wonderfully detailed articles about monsters from around the world, debates concerning their locations and histories, and a very useful classified section for monster sellers and buyers. Dr. March and Bailey’s father were frequent contributors, although they had never met each other in person.

Dougie hoped his goblin sketch would catch the eye of the editor of Peculiar and might even earn him the cover.

“I’m going to make you a star,” he whispered to Canopus, but the goblin didn’t seem to hear. He still clung to the bluebird night-light and stared at the ceiling lights. His eyes had swollen to slits from the bright light and lack of sleep. Bailey feared he might go blind.

“Dad, how long have you been up?”

“Hours, son. I was too excited to wait until morning. I hope I didn’t wake you.”

“I wish you would have. I slept yesterday away and I have my presentation today. I’ve run out of time to prepare.”

His father squeezed his shoulder and shook him. “I’m sure you’ll do fine. You can think on your feet, just like you did on the hunt when you threw the lantern to distract the goblins. You saved my life, son. Your mother would have been so proud. Just look at him, Bailey—in our possession—the infamous Gobelinus cuniculus.”

Bailey looked at Canopus’s swollen eyes and pitied him and his crazy ideas.

“Dad, you know why these goblins are obsessed with lights, right? They think the stars fell out of the sky and it’s their job to put them back.”

His father continued sketching. “How do you know that?”

“Because the female one told me so.”

His father swept the hair out of his eyes. “Don’t let a goblin fool you, son. She’ll say whatever is necessary to trick you into opening the cage. Think of them as dumb moths, drawn to lights out of instinct. And remember, if given the chance, she’ll eat your face.”

The Monster Catchers--A Bailey Buckleby Story

The Monster Catchers--A Bailey Buckleby Story